Moving Targets: The Real Strategies Behind the War on Terrorism

- June 29, 2016

- 0

by Al Hidell

“Now we have the possibility of cooperation in Eurasia. You look at the agreements among China, discussions with Japan, India, Russia, other nations; you see there’s now a thrust for cooperation in large-scale projects, and trade projects, which will build up Eurasia…Somebody wants to stop it. For various reasons, August is a good month to start a war, in Eurasia. And we’re on the edge of a war. The war is being orchestrated by people who say the only way to prevent China, Russia, India, and so forth, from cooperating in Eurasian economic cooperation is to do what? To start a war between Islam and the West.” Lyndon LaRouche, July 24, 2001

They were horrible acts that killed thousands of innocents, and the perpetrators must be brought to justice. That much is clear. Yet the tragic events of September 11, 2001 will have a multitude of repercussions that have yet to emerge.

They were horrible acts that killed thousands of innocents, and the perpetrators must be brought to justice. That much is clear. Yet the tragic events of September 11, 2001 will have a multitude of repercussions that have yet to emerge.

At this stage, it is likely that America’s War on Terrorism will have many victims – both foreign and domestic – not the least of which may be our freedom.(1) To better understand the reasons and aims of this New War, we will need to look beyond the bloodlust and comic book – level analyses offered by most of our pundits and politicians.

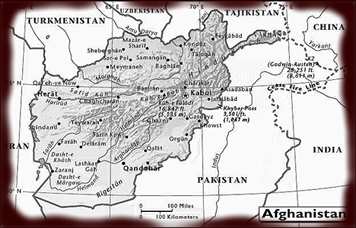

Smaller Rubble

“Basically, we’re going to bomb their rubble into smaller rubble.” This is how an unnamed congressional staffer described the start of America’s War on Terrorism, whose first military target is the impoverished and civil war – torn country of Afghanistan. The official reason is that the country’s radical Islamic rulers, known as the Taliban, have harbored and supported the presumed mastermind of the September 11 attacks: Osama bin Laden.

The apparent goals of the War on Terrorism are the death or extradition of Osama bin Laden, and the neutralization of radical Islamic regimes and networks worldwide. Yet the capture or assassination of bin Laden – who has followed Carlos the Jackal and Abu Nidal as the latest personification of World Terrorism – would likely result in more terrorism, not less. Kill one Osama, it is said, and you create 100 more. Furthermore, the military attacks against Afghanistan increase the chances of radical Islamic takeovers in countries that are supporting the US strikes, and for Pakistan you can add nukes to the scenario.

Moreover, the Taliban did not emerge in a vacuum. They were largely created and financed by Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, countries that are now being sought by America as allies in the War on Terrorism. In fact, the United States gave Afghanistan $124 million in aid in 2001, making it “the main sponsor of the Taliban,” according to the May 22, 2001 Los Angeles Times. Indeed, the United States also trained and financed bin Laden himself and other radical Islamics when it served its interests.

This latter point deserves elaboration. Media commentators are now acknowledging that the United States made a “mistake” in the 1980s by supporting bin Laden and his fellow radical Islamics against the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. This obscures the fact that the CIA flat-out created today’s violent Islamic movement as a deliberate policy. Furthermore, this policy amounted to much more than supplying the mujahedeen with some Stinger missiles, which is the popular conception of events. As reported in a laudatory 1992 Washington Post article (“Anatomy of a Victory: The CIA’s Covert Afghan War”), the United States invested more than $2 billion and several thousand tons of weaponry and supplies in the project. The covert action involved everything from supplying copies of the Koran to constructing training camps – which we are now bombing – and teaching the future terrorists how to make bombs. All in all, this “mistake” was the single largest American covert action program since World War II.

If you think arming and supporting radical Muslims was just a tragic mistake of the past, think again. Osama bin Laden and an army of what the United States would otherwise label Islamic terrorists have been and are actively involved on the US-backed side in the fighting in Bosnia, Kosovo and – most recently – Macedonia. In Issue 21 of PARANOIA (“Bankers and Generals: The Economic Interests Behind the Yugoslavian Conflict,” Fall, 1999), this writer quoted Ben Works, director of the Strategic Research Institute:

“There’s no doubt that bin Laden’s people have been in Kosovo helping to arm, equip, and train the [Kosovo Liberation Army]… The US Administration’s policy in Kosovo is to help bin Laden. It almost seems as if the Clinton Administration’s policy is to guarantee more terrorism.”

In addition, there are nations that the US State Department has officially designated as “supporting terrorism” – Cuba, Iran, Libya, North Korea, and Syria – that have no known connection to Osama bin Laden. He does, however, maintain a residence in the posh London suburb of Wembly. In fact, on Nov. 20, 1999, the London Daily Telegraph admitted:

“Britain is now an international center for Islamic militancy on a huge scale… and the capital is the home to a bewildering variety of radical Islamic fundamentalist movements, many of which make no secret of their commitment to violence and terrorism to achieve their goals. “(2)

This is not meant to obscure the fact that the Taliban of Afghanistan are currently and have recently been bin Laden’s main supporters and harborers; it is just to point out that the supposedly worldwide War on Terrorism is at this point a highly selective affair.

Nevertheless, some argue that America has been forced to take action in response to the events of September 11. As we will see, America has other little-discussed reasons – that have nothing to do with 9/11 – for wanting to control Afghanistan. Indeed, a former Pakistani diplomat told the BBC on September 18 that the US was planning military action against the Taliban well before the hijack attacks. Niaz Naik, a former Pakistani Foreign Secretary, says he was told by senior American officials in mid-July that military action against Afghanistan would take place by mid-October. The larger objective, according to Naik, is to topple the Taliban regime and install a transitional government of moderate (i.e. US-controlled) Afghans. The horrors of September 11, then, may have served as a convenient excuse to implement a preexisting Afghan war plan.

Under the Rubble

So, why Afghanistan? Although not widely discussed, the country has more than “rubble” to offer its controllers. In 1999, Afghanistan produced 75% of the world’s opium, from which heroin is derived. It should be noted that in February 2001, the fundamentalist Taliban destroyed the country’s entire opium crop. While this unprecedented action was publicly applauded by the United States, it undoubtedly put the Taliban at the top of the enemies list of those elements within the United States and abroad that profit from the global drug trade.

Despite recent alarmist news stories about bin Laden and the Taliban “flooding the US with heroin,” pre-September 11 coverage of the Afghan opium situation provides a more objective view. A February 16, 2001 Associated Press story was headlined, “Taliban virtually wipes out opium production in Afghanistan.” It stated:

“A 12-member team from the U.N. Drug Control Program spent two weeks searching most of the nation’s largest opium – producing areas and found so few poppies that they do not expect any opium to come out of Afghanistan this year.”

Of course, Taliban-controlled territory could begin to produce opium again. However, the earliest harvest date would be May, 2002. So British Prime Minister Tony Blair’s recent vow to “bomb their poppy fields” neglects the fact that there are few if any poppy fields to bomb. (However, there may well be stockpiles of last year’s harvest.)

Regarding the addictive substances known as fossil fuels, the United States Department of Energy (DOE) estimates that Afghanistan has natural gas reserves of 4-5 trillion square feet, oil reserves of 95 million barrels, and significant coal reserves as well. Today, however, these riches remain unproven and untapped due to decades-long fighting and instability. The DOE says Afghanistan also has significance from an energy standpoint due to its geographical position as a potential transit route for oil and natural gas exports from Central Asia.

This potential would require multiple multi-billion-dollar oil and gas export pipelines through Afghanistan. One of the largest is a proposed 890-mile, $2-billion, 1.9-billion-cubic-feet-per-day natural gas pipeline project led by the American energy firm Unocal. However, in December 1998, Unocal announced that it was withdrawing from the consortium, saying low oil prices and turmoil in Afghanistan made the pipeline project uneconomical and too risky. Today, there is growing pressure to begin a trans-Afghanistan pipeline, in order to preempt plans for a pipeline out of Turkmenistan via Iran.

Significantly, Unocal has stated that their pipeline project will proceed once an internationally recognized government is in place in Afghanistan. John Maresca, vice president for international relations of the Unocal Corporation, stated in an important February 12, 1998 Congressional hearing, “U.S. Interests In The Central Asian Republics,”(3): “From the outset, we have made it clear that construction of the pipeline we have proposed across Afghanistan could not begin until a recognized government is in place that has the confidence of governments, lenders, and our company.”

At the same hearing, Robert W. Gee, the Clinton Administration’s Assistant Secretary for Policy and International Affairs, Department of Energy, made no secret of the fact that “we have an interest in maximizing commercial opportunities for US firms.” Or, as Vakhtang Kolbaia, deputy chairman of the Georgian parliament, has observed regarding his own country, “Western countries understandably require security for their investments.”

Afghanistan also has geopolitical significance because it borders three Central Asian Republics of the former Soviet Union: Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Tajikstan. Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan are thought to have oil reserves; Turkmenistan also has the world’s fourth-largest natural gas reserves; and Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan border the region’s most extensive oil reserves, in Kazakhstan.

So the Taliban has become a major problem for both Big Energy and Dope, Inc., in ways that have nothing to do with terrorism.

Beyond the Pipelines

Unocal’s position on Afghanistan reflects the global energy cartel’s broad desire to bring Western-dominated stability to the Caspian Sea region, as well as the Balkans. This will make it easier for the cartel to get down to the business of exploiting the region’s considerable natural resources, which the US State Department has declared will be “crucial to the world energy balance over the next 25 years.”

In addition to an interest in energy and drug pipelines, there may be a broader US geopolitical strategy at work, one directed at our old Cold War nemesis. The authors of “Why Washington Wants Afghanistan” (4) argue that Russia remains a significant threat and competitor to the United States. The authors consider US/NATO military actions in the former Yugoslavia (the Balkans region), and the current actions in Afghanistan, to be part of a larger plan:

“Central Asia is strategic not only for oil, as we are often told, but more important for position. Were Washington to take control of these republics, NATO would have military bases in the following key areas: the Balkans, Turkey; and [the Central Asian] Republics. This would constitute a noose around Russia’s neck. Add to that Washington’s effective domination of the former Soviet Republics of Azerbaijan and Georgia, in the south, and the US would be positioned to launch externally instigated ‘rebellions’ all over Russia.”

“If the US can break up Russia and the other former Soviet Republics into weak territories,” they surmise, “Washington would have a free hand.” The War on Terrorism, these authors believe, is little more than a smokescreen. They believe that Washington, in fact, ordered Saudi Arabia and Pakistan to fund the Taliban “so the Taliban could do a job: consolidate control over Afghanistan and from there move to destabilize the former Soviet Central Asian Republics on its border.”

They conclude that the tragedies of September 11 are being used by the Bush Administration “to create an international hysteria in order to drag NATO into the strategic occupation of Afghanistan and an intensified assault on the former Soviet Union.” This, they warn, will move us closer to an all-out war with Russia.

For now, though, we know that Russian officials have charged that the Taliban aims to create “liberated zones” across Central Asia and Russia, and that they have linked their problems in Chechnya to the rise of Taliban fundamentalism (www.Indiareacts.com).These facts, along with some very positive public diplomacy that took place in mid-October, 2001, suggest that a common enemy (the Taliban) has brought Russia and the United States closer together. Some commentators have gone so far as to suggest that we are witnessing a major strategic realignment. They say relations between the two countries are the strongest since World War II, when we fought another common enemy, Nazism.

Nevertheless, Bradford University professor Paul Rogers in his book Losing Control has warned of “a near-endemic Russian perception that NATO expansion and US commercial interests in the Caspian basin are part of a strategic encroachment into Russia’s historic sphere of influence.” The key question, then, is what will happen to US/Russian relations after the Taliban is defeated, and the War on Terrorism moves beyond Afghanistan.

If one holds a darker view of Russia and its intentions, today’s Afghanistan presents the 1980s with a twist. The country is again a Cold War-style battleground, but this time the United States wants the Afghan rebels (the anti-Taliban, Russian- and Iranian-backed Northern Alliance) to lose. This would seem to conflict with the stated aims of the War on Terrorism. So, if there is a US/Russia proxy war going on in Afghanistan, it will certainly be interesting to see what becomes of the Northern Alliance.

Already, soon after the start of military action, American officials have begun to promote the idea of a “broad coalition government” for Afghanistan, while downplaying the role of the Northern Alliance. In fact, Secretary of State Colin Powell recently in Pakistan offered a place in the new Afghanistan government for “moderate” Taliban leaders. Before we make too much of this, it should be noted that the Northern Alliance is made up of Afghan ethnic minorities, and the US may have genuine concerns that the country’s ethnic majority would never support a Northern Alliance-based government.

What About China?

A major regional player not considered in the above analysis is China, which has been using military force to keep order in its Xinjiang province, where Muslim Uighur separatists have been fighting for independence. At this point, the massive, nuclear-armed Communist state is providing mixed signals, with modest words of support for the War on Terrorism, and also some little-reported warnings against US military action. China has said it opposes any unilateral military action in Afghanistan, and wants the United Nations to authorize any attacks. Also, it may be significant that Afghanistan’s U.N.-recognized government-in-exile is located in Beijing, China (Reuters, September 12, 2001).

On October 4, 2001, the Washington Times reported that China had placed its military forces in the western part of the country on heightened alert and was moving troops to the border region near Afghanistan in anticipation of the US military strikes. The Frontier Post, an English-language newspaper published in Peshawar, Pakistan, reported October 1 that Chinese military forces had begun exercises near the Afghan border. Clearly, the intent is to suggest that China will enter the war on the side of the Taliban.

However, China would seem to have little motivation to support the Taliban. In fact, by coincidence two days after September 11, its 15-year struggle was rewarded when it was announced that China would be admitted into the World Trade Organization (WTO). China’s recent successful campaign to host the Olympic Games is further evidence that the country wants to become part of the Western capitalist order, rather than destroy it. There is no doubt that there is already great economic interdependence between China and the United States, and that many US businesses are committed to strong economic relations with China.

On the other hand, September 11 was also the day China signed a memorandum of understanding with the Taliban for greater economic and technical cooperation. (Washington Post, September 13, 2001) Also, on October 18 the Associated Press made an unconfirmed report that bin Laden Deputy Abu Baseer al-Masri was killed by a bomb in eastern Afghanistan, and that “two of his comrades, a Chinese Muslim and a Yemeni, were injured.” It is quite a leap, though, to go from one Chinese Muslim to the “5,000 to 15,000” reported by Israeli intelligence site www.debka.com. However, if these numbers are ever confirmed, the Chinese Muslims must have at least the tacit approval of Beijing. If China believes that the strategic realignment between Russia and the United States referred to above is taking place, it may well feel threatened enough to take these kinds of actions.

Support From the Outside

It is strange that there has been relatively little domestic media attention given to the role of China in the War on Terrorism, as well as that of Russia and India. These three countries, after all, are by far the largest and most powerful states in the Afghan region, and all are members of the Nuclear Club. Iran, too, has been a major player in Afghanistan, and the two nations share a long border.

So why have these countries been missing in much of the mainstream discourse about the War on Terrorism? Perhaps the US government believes that these countries will become players in a larger war. In that case, our leaders would likely prefer that the American public stay in the dark about such complexities, lest public support for the War on Terrorism erode. The more limited and straightforward goal of punishing those responsible for the September 11 attacks is a much easier sell.

Prior to September 11, such complexities were readily acknowledged. At the above referenced 1998 Congressional hearing (“U.S. Interests In The Central Asian Republics”), Rep. Dana Rohrabacher of California observed, “At this point, you have got the Pakistanis and the Saudis on one side, and you have got the Iranians on one side. Every little faction has somebody who is supporting them from the outside.” Likewise, Committee Chairman Rep. Doug Bereuter of Nebraska noted that “Japan, Turkey, Iran, Western Europe, and China are all pursuing economic development opportunities and challenging Russian dominance in the region. It is essential that U.S. policymakers understand the stakes involved in Central Asia…”

Rep. Howard L. Berman of California defined the United States’ major adversaries in the area as Iran and Russia, a sentiment that seemed to be shared by most of the Committee: “American interests in the region are simply to ensure its progressive political and economic development and to prevent it from being under the thumb of any outside power, be it Iran or Russia.”

This concern was echoed by the Department of Energy’s Robert W. Gee:

“Rep. Berman. [You have said] our support for this pipeline derives from our belief that it is not in the commercial interests of companies operating in the Caspian States nor in the strategic interest of the host States to rely on a single major competitor for transit rights. Who are you talking about?

Mr. Gee: “We are talking specifically about Russia and Iran, which would be potentially the two dominant players where most of the transit routes [would be] situated.”

If anyone missed the point, Assistant Secretary Gee then stated, “The US government’s position is that we support multiple pipelines with the exception of the southern pipeline that would transit Iran.” However, he was more conciliatory regarding Russia:

“Our Caspian policy is not intended to bypass or to thwart Russia…We support continued Russian participation in Caspian production and transportation. We would also welcome their participation in the Eurasian corridor. US companies are working in partnership with Russian firms in the Caspian, and there will be future opportunities to expand that commercial cooperation.”

The United States government clearly viewed Iran as the greatest threat in the region. This, despite the testimony of hearing witness Frederick Starr, Chairman of the Central Asia Institute at Johns Hopkins University. Mr. Starr noted that early Iranian efforts to “export” its radical Islamic revolution had completely failed:

“In the early years after the independence of the Central Asian and Caspian States, Iran did indeed attempt quite vigorously to export its revolution and its ideology to the region. It pressed quite hard in some places, but without success. In fact, the uniformly secular regimes of Central Asia and the Caspian firmly told them, ‘No. We’re glad to trade with you, but keep your ideology at home.'”

Furthermore, Mr. Starr declared that “none of our friends in the region agree” with the US position against economic engagement with Iran. He noted that French, Malaysian, and Russian firms were already investing in the construction of facilities in Iran, and that a pipeline was already being constructed across northern Iran from Turkmenistan. “The American [economic] quarantine of 1995-1996,” he advised, “is not holding.” Finally, Mr. Starr pointed out that Iran’s historic election of a moderate and at least somewhat pro-western leader, President Khatami, was making the US policy of sanctions much harder to defend.

Shifting Alliances

Of course, this Congressional hearing was conducted during the Clinton Administration, and we don’t know how much things have changed under the Bush Administration. There has, though, been an obvious shift away from President Clinton’s conciliatory and cooperative attitude towards China, into a more adversarial relationship. Similarly, the Clinton Administration’s strong tilt towards India at the expense of its bitter enemy Pakistan has been reversed by the Bush Administration’s embrace of Pakistan as its leading ally in the War On Terrorism.

However, despite continued conciliatory statements from Iranian President Khatami, it appears that the US government’s hard- line attitude towards Iran has remained unchanged. This is suggested by an October 18, 2001 report (www.worldtribune.com) that “the United States has rejected Iran’s offer to aid the US-led offensive against the ruling Taliban in Afghanistan.” The report says that US Secretary of State Colin Powell termed the offer by Iran – which has condemned the September 11 attacks, and which has long opposed the Taliban – as “not necessary.” This, from an administration that has gone out of its way to court allies of all stripes and shades in its War On Terrorism.

Of course, public rejections and a dearth of news stories may be masking behind-the-scenes cooperation between Washington and Iran, as well as with Russia and India. As early as June 26, 2001, an Indian public affairs web site (www.Indiareacts.com) was reporting that “India and Iran will ‘facilitate’ the planned US-Russia hostilities against the Taliban.” (The American people, it seems, were the last to know about America’s New War.) The article reports that Secretary of State Powell laid the groundwork for this cooperation in meetings with his Russian and Indian counterparts. No mention is made of any US-Iranian meetings, although Iran is said to have participated in an unspecified “series of discussions” with Russia and India.

All in all, it seems that Russia, India, and Iran are supportive of the US military action against the Taliban, while China – as is often the case – is a question mark. All four countries are dealing with Taliban-supported fundamentalist Muslim insurgencies to one degree or another. If the War on Terrorism extends beyond Afghanistan, however, their continued support is far from certain.

The Strategic Triangle

Capitalism is about economic competition, and trade wars sometimes become shooting wars. Likewise, economic alliances often become military alliances. With this in mind, it may be instructive to consider recent developments involving China, Russia, India, and Iran, and see if the seeds of a wider conflict are present.

The New Federalist newspaper (www.larouchepub.com) is one of the few non-specialist publications to cover economic developments in the region. On June 25, 2001, it reported that Russia and China – along with Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan – had formed the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). Representing 1/4 of the world’s population, the SCO is said to be based on a commitment to collaboration and cooperation in economic and security matters. Ironically, the SCO grew out of a 1999 agreement in which the countries vowed to work together to counter the threat of Islamic terrorism.

Regarding the Russia-China partnership, the New Federalist stated that relations between the two countries have been developing over the last three years; and that “the outline of the concept of the Strategic Triangle – Russia, China, India – [proposed] by Russia’s former Prime Minister Yevgeni Primakov in 1998, has gradually been filled in, at least on the Russia-China leg of the triangle.”

Furthermore, in July, 2001, Russia and China signed a “Good Neighborly Friendship Cooperation Treaty,” which promises extensive military and economic cooperation. The countries have also been united in their opposition to implementation of President Bush’s National Missile Defense system, which they think will encourage the US to launch a nuclear first strike against them during a time of conflict.

In addition, on October 18, 2001 (www.worldtribune.com), it was reported that relations between India and Iran were advancing rapidly. Though not widely reported, for the first time, Iran and India have held strategic cooperation talks:

“India’s Foreign Secretary Chokila Iyer and Iranian Deputy Foreign Minister for Asia and Pacific Mohsen Aminzadeh discussed security and defense issues. The two officials also discussed international disarmament and security cooperation and the situation in Afghanistan.”

In addition, Middle East Newsline (www.menewsline.com) has related a Washington Times report that China is currently building an air defense network along Iran’s border with Afghanistan, and that “China is said to have accelerated strategic and military projects in Iran over the last year,” including “help for Iran’s intermediate- and long-range missile systems.”

As stated previously, the Washington Times appears to be promoting the idea of a major Chinese threat. Yet it is quite plausible that China is helping Iran, especially in light of the ongoing US Iranian sanctions. India and Russia, too, are partnering with Iran on at least one major economic project, what Indiareacts has characterized as “a broad plan to supply oil and gas to south Asia and southeast Asian nations through India.”

Furthermore, the London-based Arabic daily Al Hayat reported on October 9, 2001 that Iran’s Defense Secretary would be visiting Russia within a week to sign a weapons deal that will include “anti-aircraft defense systems and tanks.” Russian Defense Minister Sergei Ivanov was reported as stressing that Russia is interested in developing the “military, economic and scientific relations with its neighbor Iran.” This relationship, according to an editorial in the March 5, 2001 Guardian (UK), includes Russia providing Iran with “nuclear know-how.”

Flashpoint

So, is Iran the flashpoint that could bring the Russian Strategic Triangle of Russia, China, and India together against the United States? This frightening prospect is supported by an October 18, 2001 item on Middle East Newsline:

“Russian officials said Moscow would help Washington with the war on terrorism. But they said President Vladimir Putin would not allow the regime of Iraqi President Saddam Hussein or Iran to become a US target in such a war. Both Iran and Iraq are on the US State Department list of terrorist sponsors, [and] Moscow has indicated that this is where it would draw the line. Russia has emerged as an ally of both Baghdad and Teheran.”

The article quotes Col. Sergei Goncharov, a leading Russian military analyst, as saying, “We can’t allow the United States to wield its club the way it wants.” He continues, “We are on good terms with Iran. We have tremendous economic investments in and expectations of Iraq. We can’t afford to sever all these ties in one stroke. I foresee a major debate along these lines.”

A debate, or a war? While Goncharov allowed for the possibility of limited air strikes against Iraq if there is proof that they are harboring terrorists, he made no such allowance regarding Iran. Regarding either country, the Russian Colonel warned, “If they want to start carpet bombings, like in Yugoslavia, and then see what happens, it can’t be allowed.”

World War III?

So, will the War on Terrorism become World War III? Al Hayat reported on October 9, 2001 that US tactical nuclear weapons are already in Afghanistan. Ranging in power from 2 to 10 kilotons, they are said to be considered a “last resort” by American military planners. So, there is certainly the potential for a dangerous escalation of hostilities.

Fears of a geographically-larger war were certainly not calmed by an October 21, 2001 Reuters report that Air Force Gen. Richard Myers, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, considered Afghanistan to be “only a ‘small piece’ of what he suggested might be the broadest campaign since World War Two, possibly lasting more than a lifetime.” Myers, America’s top military commander after the President, added, “I think this is going to be a long, hard-fought conflict, and it will be global in scale.”

Similarly, on October 3, www.newsmax.com quoted General Jack Singlaub, former chief of staff for US forces in South Korea: “I think the war is going to broaden. I think that the president made it quite clear that this is a pure case of good vs. evil and those who want to live in peace must unite and eliminate those who want to kill one another.” He added ominously, “We just have to recognize that it’s going to develop into a larger war, and there [will be] lots of people and nations involved.”

Endnotes

(1) The September 17, 2001 USA Today warned, “Israelis and Europeans are used to seeing machine gun-toting soldiers… stopping them at checkpoints. Soon, Americans may become accustomed to the sight also.” Meanwhile, CNN has broadcast footage of National Guardsmen training at a mockup of a guard station with a road barrier and a sign that reads “Homeland Security Internal Checkpoint.”

(2) For a surprising and detailed argument to “Put Britain on the List of States Sponsoring Terrorism,” see www.larouchepub.com.

(3) House Committee Report, http://commdocs.house.gov/committees/intlrel/hfa48119.000/hfa48119_0.HTM

(4) Jared Israel, Rick Rozoff and Nico Varkevisser, “Why Washington Wants Afghanistan,” posted September 18, 2001 to www.emperors-clothes.com.