The Deadly Bermuda Triangle

- November 18, 2017

- 0

by Vincent H. Gaddis

Argosy February 1964

What is there about this particular slice of the world that has

What is there about this particular slice of the world that has

destroyed hundreds of ships and planes without a trace?

With a crew of thirty-nine, the tanker Marine Sulphur Queen began its

final voyage on February 2, 1963, from Beaumont, Texas, with a cargo

of molten sulphur. Its destination was Norfolk, Virginia, but it

actually sailed into the unknown. A routine radio message on the

night of February third placed the ship near the Dry Tortugas.

The 254-foot vessel was overdue on February sixth, and a search was

launched for it. Planes took off from Coast Guard stations from

Florida to Viginia, while cutters patrolled the Atlantic coast. When

no trace was found, the search was abandonned on February fourteenth.

Five days later, in the Florida Straits, fourteen miles southeast of

Ket West, a Navy torpedo retriever picked up a life jacket and several

bits of debris believed to have come from the tanker. Nothing more

has been found.

On August 28, 1963, two KC-135 four-engine strato-tanker jets took off

from Homestead AFB, south of Miami, Florida, on a classified refueling

mission over the Atlantic. The crews totalled eleven men. The

weather was clear.

At noon, the planes radioed their position as 800 miles northeast of

Miami and 300 miles west of Bermuda. The planes were new, in radio

contact with each other and they were not flying close together,

according to an Air Force spokesman.

Then the planes vanished.

An extensive search was launched. Planes criss-crossed the area in

formation, following a carefully planned pattern of observation.

Vessels churned the surface of the sea.

On the following day, debris was discovered floating on the water

about 260 miles southwest of Bermuda. No survivors or bodies were

found.

It was presumed that the two planes had collided in the air, but two

days after the disappearance, more debris was located — but it was

160 miles from the first discovery. What happened remains a mystery.

The mysterious menace that haunts the Atlantic off our southeastern

coast had claimed two more victims. Before this article reaches

print, it may strike again, swallowing a plane or ship, or leaving

behind a derelict with no life aboard.

Other recent cases:

Two months earlier, on July first, the sixty-three-foot fishing boat

Sno’ Boy, under U. S. registry, sailed from Kingston, Jamaica, for

Northeast Cay, a small island eighty miles southeast of Jamaica.

Forty persons were aboard.

When it was overdue, the U. S. Navy and Coast Guard launched a search.

Several bits of debris believed to be from the vessel were observed.

Finally, after ten days, the search was abandonned.

On January 8, 1962, a KB50 Air Force tanker rolled down a runway at

Langley AFB, Virgina, and headed east, bound for the Azores. Major

Robert Tawney was in command of the crew of eight men.

A short times later, the tower at Langley received weak radio signals

from the plane. Then the signals faded into silence.

Again, there was an extensive search, but there was no trace of

wreckage or of bodies. After 1700 fruitless man-hours, the search was

ended.

During the past two decades alone, this sea mystery at our back door

has claimed almost 1,000 lives. But even this is only as inference.

In this series of disasters, not one body has ever been recovered.

U. S. Navy, Air Force and Coast Guard investigators have admitted they

are baffled. The few clues we have only add to the mystery.

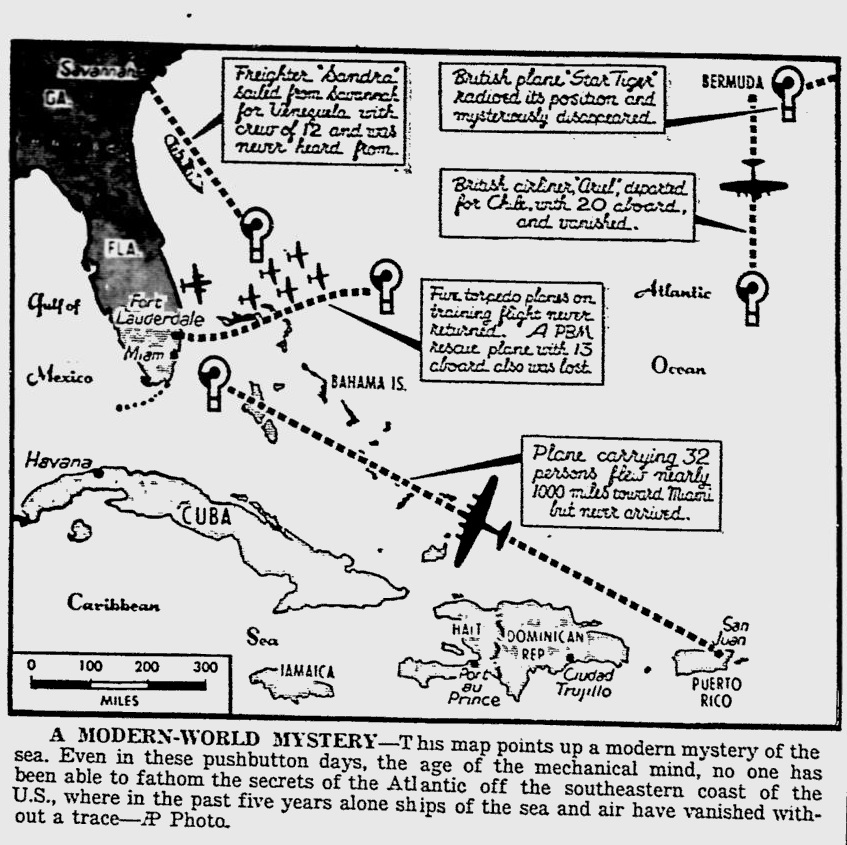

Draw a line from Florida to Bermuda, another from Bermuda to Puerto

Rico, and a third line back to Florida through the Bahamas. Within

this area, known as the “Bermuda Triangle,” most of the total

vanishments have occurred.

This area is by no means isolated. The coasts of Florida and the

Carolinas are well populated, as well as the islands involved. Sea

distances are relatively short.Day and night, there is traffic over

the sea and air lanes. The waters are well patrolled by the Coast

Guard, the Navy and the Air Force. And yet this relatively limited

area is the scene of disappearances that total far beyond the laws

of chance. Its history of mystery dates back to the never-explained,

enigmatic light observed by Columbus when he first approached his

landfall in the Bahamas.

The Bermuda Triangle underlines the fact that despite swift wings and

the voice of radio, we still have a world large enough so that men

and their machines and ships can disappear without a trace.

Whatever this menace that lurks within a triangle of tradgedy so

close to home, it was responsible for the most incredible mystery

in the history of aviation — the lost patrol. Here is the amazing

story:

Early on a Wednesday afternoon, five TBM Avenger torpedo bombers

lined up on runways at the Fort Lauderdale (Florida) Naval Air

Station. The date was December 5, 1945.

Normally, the Avengers carried a crew of three — a pilot, a gunner

and a radio operator. One crewman, however, failed to report this day.

The bombers had been carefully checked and fueled to capacity. The

engines, controls, instruments and comapsses were in perfect condition,

according to later testimony. Each plane carried a self-inflating

life raft and each man was equipped with a life jacket. All fourteen

men had flight experience ranging from thirteen months to six years.

At two minutes past two p.m., the flight leader closed his canopy,

gunned his engine, and the first plane roared down the runway.

The others followed in quick succession, climbing up into the clear

sky and heading east over the Atlantic at 215 mph.

It was a routine patrol flight. The navigation plan for the formation

was to fly due east for 160 miles, then north for forty miles, then

back southwest to the air station, completing a triangle. The relatively

short flight would require about two hours.

The first word from the patrol came to the base control tower at

three forty-five, but the strange message did not request the expected

landing instructions.

“Calling tower, this is an emergency,” the patrol leader said in a

worried voice. “We seem to be off course. We cannot see land …

repeat … we cannot see land.”

“What is your position?” the tower radioed back.

“We are not sure of our position,” came the reply. “We can’t be sure

where we are. We seem to be lost.”

Startled, the tower operators looked at one another. With ideal flight

conditions, how could five planes manned by experienced crews be lost?

“Assume bearing due west,” the tower instructed.

There was unmistakalbe alarm in the flight leader’s voice when he

answered. “We don’t know which way is west. Everything is wrong …

strange. We can’t be sure of any direction. Even the ocean

doesn’t look as it should.”

Let’s suppose that the patrol had run into a magnetic storm that caused

deviations in their compasses. The sun was still above the western

horizon. The flyers could have ignored their compasses and flown west

by observation of the sun.

Apparently not only the sea looked strange, but the sun was invisible.

During the next few minutes, the tower operators listened in as

the pilots talked to one another. The conversation progressed from

bewilderment to fear, verging on hysteria.

Shortly after four p.m., the flight leader suddenly turned over flight

command to another pilot.

At four twenty-five p.m., the new flight leader contacted the tower.

“Tower,” he said, “we are not certain where we are … we think we

must be about two hundred and twenty-five miles northeast of base.

It looks like we are …” The message ended abruptly.

That was the last word from the doomed patrol.

Tower operators signaled a rescue alarm. Within a few minutes, a huge

Martin Mariner flying boat with full rescue and survival equipment

and a crew of thirteen men was on its way.

The tower tried to call the Avengers to tell them help was en route.

There was no reply.

Several routine radio reports were received from the Mariner. About

twenty minutes after it left the base, the tower called the flying

boat to check its position. There was no answer.

What was happeneing out there over the sea 200 miles away?

By this time, it was dusk. Alarmed, operations at Fort Lauderdale

notified the Coast Guard at Miami. A Coast Guard rescue plane

covered the flying boat’s route and reached the last estimated position

of the missing patrol. There was not a sign of the six planes.

Navy and Coast Guard vessels joined the search. Through the long

night, they watched for possible signal flares from life rafts.

But no lights broke through the darkness above the black sea.

At dawn, the escort carrier Solomons moved into the area and dispatched

its thirty planes in an aerial search. Within a few hours, twenty-one

vessels were combing the sea. Above the ships were 300 planes flying

in grid search pattern. The British Royal Air Force pressed every

available ship into service from the nesrby territorial islands. All

during the day, the sky and the sea were methodically criss-crossed over

an ever-widening area.

The intensive search continued on the following day, not only between

Florida and the Bahamas, but 200 miles into the Gulf of Mexico. Twelve

large land parties searched 300 miles of shoreline from Miami Beach

to St. Augustine. Low-flying planes checked beaches south to Key West

and north to Jacksonville. But not a scrap of wreckage or debris was

found.

Military experts were baffled. How could six airplanes (including the

large Mariner) and twenty-seven men totally vanish in such a limited area?

Did the planes eventually run out of fuel? While the Avengers were not

especially buoyant, the Navy said they would remain afloat long enough

for life rafts to be launched, and the crewmen “shouldn’t even get

their feet wet.” All the missing men were trained in sea-survival

procedures and had Mae West life jackets. After similar ditchings,

Navy crewmen had existed for days, even weeks, in open sea.

Each plane had its own radio facilities. Why was no SOS received

from at least one of the planes?

Commander H. S. Roberts, executive officer at the base, suggested that

his fliers might have been blown off course by high winds. The Miami

Weather Bureau reported that there had been gusts up to forty mph in

the general area where the patrol was last reported. These winds

would not seriously influence flying.

A waterspout would affect only a low-flying plane. But if a freak

waterspout had struck the partol, there would certainly

have been debris.

And what about the Mariner? Did it meet the same fate as the patrol?

All these theories disregard the puzzling circumstances reported by

the flight leader: the curious observations and the strange inability

to determine location.

On the night of the disappearance, the S.S. Gaines Mills, a mercahnt ship,

notified the Navy that it had observed an explosion high in the sky at

seven-thirty p.m. No wreckage or oil slicks were found at the location

given. But the explosion occurred more than three hours after the last

radio message from the patrol, and it is unlikely that there is a

connection. It may have been an exploding meteor.

“They vanished as completely,” an officer of the Naval Board of Inquiry

said, “as if they had flown to Mars.”

A study reveals some possible clues.

If the patrol had flown west, they would have reached Florida of the

Florida Keys. If they had flown east, they would have seen the

Bahamas; Grand Bahama is almost twenty-five miles long. Southeast

were the Great Abaca and Andros islands. Open areas were north and south,

but on such a clear day, islands and the mainland should have been

visible part of the time.

We can only conclude that the patrol planes were flying in a circle

between Florida and the Bahamas. This would mean that all five compasses

were thrown off erratically to the same degree. If the errors had been

constant, they would have flown straight and seen land somewhere.

Something affected the compasses; and it may also, later, have silenced

the patrol’s radios. The twin-engine Mariner not only had the usual

radio facilities, but a hand-cranked generator for emergencies.

Combine these facts with the strange appearance of the sea, plus inability

to see the sun, and a possible theory is an unknown type of atmospheric

aberration. This aberration might be called “a hole in the sky.” Its

exact nature and why it is localized to semi-tropical waters within

and near the Bermuda Triangle are not known.

Officially, the Navy does not go along with this theory. Captain E. W.

Humphrey, co-ordinator of aviation safety, puts it this way: “It is not

felt that an atmospheric aberration exists in this area, nor that one

has existed in the past. Fleet aircraft-carrier and patrol-plane

flight operations are conducted regularly in this same area without

incident.”

The fact that patrol operations are made without incident is no evidence

against the phenomenon. It is obvious that it occurs only occasionally

in the well-traveled triangle area, without warning, but frequently

enough to be alarming.

Many commercial pilots who fly the triangle consider the aberration

theory seriously. How else, they ask, can you explain what has been

happening?

As for magnetic disturbances that can affect compasses, the U. S. Navy’s

Project Magnet is currently studying this phenomenon. Super Constellations,

equipped with highly sensitive magnetometers, are covering much of the

globe searching for magnetic anomalies or unusual variations.

Although the project is classified, it has been reported that peculiar

magnetid forces coming from above have been detected in the Key

West-Caribbean area.

A similar project, combining studies of magnetism with gravity, was

authorized by the Canadian government in 1950. The late Wilbert B.

Smith, an electronics expert at Ottawa, who was in charge of the project,

claimed to have discovered regions of what he called “reduced binding”

in the atmosphere with an instrument he devised.

Smith alleged that such regions had been found at locations where there

had been unexplained plane crashes. They were described as roughly circular,

up to 1,000 feet in diameter, and probably extending upward quite a

distance. They appeared to be more common in the southern latitudes.

“We do not know if the regions of reduced binding move about or just fade

away,” Smith wrote. “However, we do know that when we looked for several

of them after three or four months we could find no trace of them.”

Smith believed that while many planes would not be affected by these

regions, others might experience turbulence that would disintegrate them.

Project Magnet may well be investigating the theories of Smith as part

of the research it is doing.

Let’s take a look at what else has happened in the area:

There was the DC-3 passenger plane, operated by Airborne Transport,

Incorporated, and chartered for a predawn flight from San Juan, Puerto

Rico, to Miami.

It was December 28, 1948, when Captain Robert Linquist, of Fort Meyers,

Florida, maneuvered the big airliner above the San Juan airport and

headed for Florida, 1,000 miles distant. The thirty-two passengers,

including two babies, had been spending the Christmas holidays on the

island. Ernest Hill, Jr., of Miami, was co-pilot. Mary Burks, of Jersey

City, the stewardess, served coffee and cookies to the passengers.

Everyone was in a gay mood. “What do you know?” Captain Linquist

reported early on the flight. “We’re all singing Christmas carols.”

Several hours passed. By this time, most of the passengers had fallen

asleep in the now-darkened cabin. Below the smoothly humming plane,

dim in the starlight, the Florida Keys began to slip by. They were

almost home.

At four-thirteen a.m. Captain Linquist made his last contact with the

Miami control tower: “We’re approaching field,” he said. “Only fifty

miles out, to the south. All’s well. Will stand by for landing

instructions.”

And then suddenly — seconds later — it happened!

It happened so swiftly that Captain Linquist and his co-pilot had no

time to send an SOS. It happened so close to the mainland that the

lights of Miami could be seen as a glow in the night sky ahead.

What is this doom that can strike a huge airliner sol quickly, so close

to home? What dread fate actually came to the men, women and infants

aboard the DC-3?

The pilots were veterans, well acquainted with the area. The U. S.

Weather Bureau said flying conditions were ideal, that there was no

likelyhood the plane had been forced down by bad weather.

Again, there was a search. Forty-eight Coast Guard, Air Force and Navy

vessels joined in carefully covering the area, fanning out from the

plane’s last reported position. In much of this region, the sea is so

shallow that any object the size of the transport can be seen on the bottom.

Again, planes crossed and ccrisscrossed the area, flying almost wingtip to

wingtip. They watched for debris, for groups of sharks or barracuda.

Eventually the searchers scanned 310,000 miles of sea and land, including the

Caribbean and Gulf areas, the Keys and the Everglades. Nothing was ever found.

The limbo of the lost that claimed the DC-3 and its passengers was on map

charted by man.

Why the planes of the British-South American Airways were especially plagued

by disappearances is a mystery within a mystery. The company was merged a

few years later with the British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC).

Earlier, in 1947, one of its airliners, the Lancastrian Star Dust, was on

the London-Santiago route. It didn’t vanish in the Bermuda Triangle, but

in Chile, leaving behind a classic enigma of the skyways.

The Star Dust was due to land at the Santiago Airport at five forty-five p.m.

on August second. At five forty-one, Captain R. J. Cook, the pilot,

radioed his arrival time. There was a brief pause, then came the word

“Stendec,” loud and clear. The strange word was twice repeated. Then silence.

The Star Dust was never heard from again. No wreckage was ever found.

Nor has anyone ever explained the meaning of the cryptic word, “Stendec.”

The next victim of the jinx was a ship.

The Sandra, a freighter, 350 feet long, radio-equipped, sailed from Savannah,

Georgia, in June, 1950, for Puerto Cabello, Venezuela. Heading south, she

passed Jacksonville and St. Augustine along the well-traveled coastal

shipping lane.

Then she disappeared as completely as if she had never existed, in the tropic

dusk, just off the Florida coast.

There was another futile search by air and sea. No debris or bodies were

ever found, in the sea or on the beaches.

In October, 1954, a U. S. Navy Super-Constellation disappeared, just north

of the Bermuda area. There were forty-two people aboard. Although the

plane had two transmitters, no radio signals were received. There was no

trace of debris or bodies, though hundreds of planes and ships searched

for days.

Commander Andrew Bright, head of the Navy’s Aviation Safety Section, admitted

that the Navy had no explanation for the disappearance.

Another Navy patrol bomber flew into oblivion near Bermuda on November 9,

1956. No radio signals were received.

There were two strange incidents in 1957 that may relate to our mystery.

On March ninth, a Pan-American World Airways DC-6 en route from New York

to San Juan nearly collided in flight with a mysterious luminous object off

the Florida coast near Jacksonville.

Captain Matthew Van Winkle pulled back on the controls and shot his plane

upward sharply to avoid the object.

Air Force officials pointed out that the location was far from the guided-missile

range. A number of other pilots in the area observed the object.

If the collision had occurred, would the plane have been added to our list of

lost airliners?

Meanwhile, the hoodoo of the triangle was not neglecting surface vessels.

In September, 1955, the yacht Connemara IV, of New York registry, was found

abandonned 400 miles southwest of Bermuda.

Al Snyder, internationally famous jockey, and two friends sailed from Miami on

March 5, 1948, to go fishing. They anchored their cabin cruiser near Sandy

Key and left in a small skiff to fish in the surrounding shallow shoals.

They never returned.

The skiff was finally found lodged by an unnamed island near Rabbit Key,

sixty miles north from the cruiser. Rewards of $15,000 were offered for

rescue of the men or recovery of their bodies. A blimp was even chartered

to join the Army helicopters and planes.

But Snyder and his companions were never seen again.

Actually, the disappearance of vessels and ships found abandonned with no

life aboard, in or near the triangle, goes back for more than a century.

It is only recently, in the air age, that these occurrences have increased

with the addition of aircraft. Atmospheric aberrations of some sort might

include the loss of ships, but would hardly cause the disappearance of crews

aboard unless the ships were abandonned in panic. Since no survivors have

been found to tell their stories, the mystery still remains unsolved.

On abandonments, my own incomplete records go back to 1840, when the Rosalie,

a French ship bound for Havana, was near the triangle. Her sails were set,

everything shipshape. The only living thing aboard was a half-starved,

caged canary.

In 1881 occurred the most incredible disappearance of crews on record.

The ellen Austin, an American vessel, was “west of the Azores” when she

found a schooner that had been deserted for no apparent reason. Everything

was in order, and there was “evidence of a struggle.”

To claim salvage, a crew from the Ellen Austin was placed aboard and the two

ships started for port. Then a squall blew up an separated the ships. When

the schooner was found, she was again deserted. The new crew had vanished.

Another crew was finally persuaded to go aboard. Again a squall separated the

vessels — and the schooner and the men were never seen or heard of again.

Vessels found strangely abandonned in or near the triangle during the present

century include the Carol Deering that ran aground at Diamond Shoals, North

Carolina, in 1921; the John and Mary, discovered fifty miles south of Bermuda

in 1932, and the Gloria Colite, of St. Vincent, British West Indies, found in 1940.

Fourteen months before the disappearance of the Navy patrol from Fort Lauderdale,

the Cuban freighter Rubicon was sighted by a Navy blimp off the coast of Florida

near Miami with only a dog aboard. It was in perfect condition, with the personal

possessions of the crew intact.

Total disappearances of vessels have been more frequent than mystery derelicts,

beginning with the schooner Bella in 1854.

In 1880, the British Atalanta, a traiing ship, sailed from Bermuda and

vanished with 250 cadets and sailors aboard.

Skipping ahead to 1918, there occurred, within the triangle, the most amazing

disappearance of a vessel in American naval annals. This was the U.S.S. Cyclops,

a Navy supply ship, 500 feet long, with a 19,000-ton displacement. When she

sailed from Barbados, British West Indies, on March fourth, for Norfolk, she

had 309 aboard and a cargo of 10,800 tons of manganese. The weather was

excellent.

No radio messages were ever received. No trace of wreckage was ever found.

Seven years later, the cargo steamer Cotopaxi, Charleston to Havana, vanished.

And a year later, in 1926, the freighter Suduffco sailed south from Port

Newark into the limbo of the lost.

The sea guards well her secrets.